Outrage, 2010

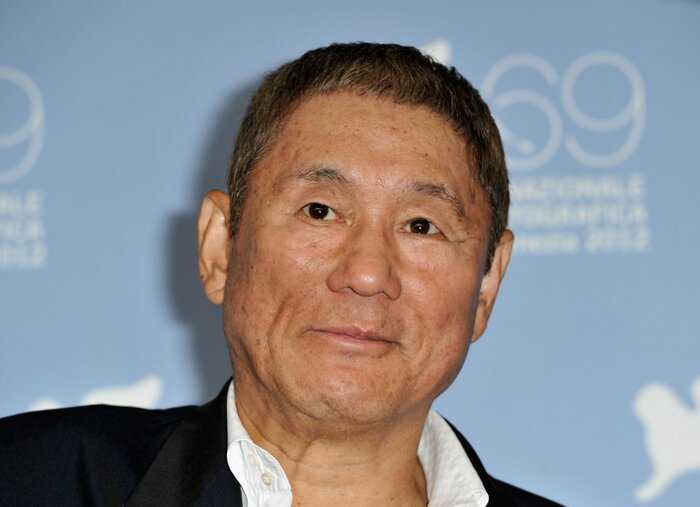

“The days are over for old-school yakuza” utters one player in this long-overdue entry that would return Kitano to the gangster genre for the first time in a decade. The phrase rings true for the director himself. While seen by many as a return to form, Outrage presents a stylistic departure from the more poetic works that had coloured the director’s reputation in the 90s.

Having scored a hit to the tune of $23.8 million with his 2003 reboot of Zatoichi, a long-running franchise about a blind swordsman, Kitano was bent on creating another blockbuster. He was modestly successful. After competing for the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2010, Outrage brought home $8.5 million in worldwide box office sales, and spawned two lucrative sequels.

Modelled more on Western gangster films than his previous works, Outrage sheds much of the idiosyncratic tropes of Kitano’s earlier works – but for a glossy and slick crime epic, it ticks all the boxes. It sees the return of Kitano’s stoic hard-man as a yakuza lieutenant caught in a war of families and features a multitude of violent slayings as its cornerstones. With some outstanding performances by genre heavyweights Jun Kunimura (Kill Bill) and Renji Ishibashi (Audition), this Japanese Godfather is extremely satisfying, if not a little conventional.

Violent Cop, 1989

While Nagisa Ōshima had opened the door for Kitano’s acting career in 1983, casting him opposite David Bowie in Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence, it was another much-celebrated Japanese director who would pass the torch to Kitano for his directorial debut.

Kinji Fukasaku, famed for his gangster franchise Battles Without Honor or Humanity, had initially signed on to direct 1989’s Violent Cop with Kitano as lead actor. But when the veteran stepped away from the production, directorial duties were left to the film’s celebrity star. A decade later, Fukasaku would memorably cast Kitano as the antagonist schoolteacher of dystopian cult hit Battle Royale – but for now, Violent Cop was an opportunity for Kitano to show his chops as a director.

На Венецианском кинофестивале настала очередь восточного кино

После показа фильмов двух американских режиссёров — «Мастера» Пола Томаса Андерсона и «К восхищению» Терренса Малика — настал черёд представления работ двух восточных тяжеловесов кинематографа – Такеши Китано, который привёз в Венецию криминальный боевик «Беспредел 2» и Ким Ки Дука с драмой «Пьета». Боевик о разборках мафии был принят зрителями скептично. Некоторых он озадачил и даже поставил в тупик, фильм заметно отличается от самых известных работ режиссёра. Большой интерес у публики вызывает картина «Пьета» Ким Ки Дука — это первый игровой фильм корейского режиссёра после долгого перерыва.

Венеция неоднозначно приняла фильм Такеши Китано

«Беспредел 2» — боевик о разборках группировок мафии, в которых замешана полиция. Главный герой картины выходит из тюрьмы и пытается наладить свою жизнь. Якудза делает всё, чтобы его завербовать. Персонаж Китано понимает, что всё-таки он один из них и мирится со своей судьбой. Речь идёт о специфическом японском исполнении: минимум слов и эмоций на лицах актёров. Мимика заметна только во время диалогов, но слова и жесты занимают в фильме небольшое время. Такая стилистика вызвала у публики недоумение. На пресс-конференции с Такеши Китано вопросы журналистов не были лишены ехидства, многие не поняли, зачем режиссёр привёз фильм на кинофестиваль.

Фильм «Пьета» — новую работу Ким Ки Дука все ждут с большим интересом, гадая, что их будет ждать на экране

Недосказанность осталась и после показа фильма «Что-то в воздухе» Оливье Ассайаса. Лента была хорошо принята зрителями. В картине затрагиваются события 1968 года. Режиссёр воссоздал то время, рассказывая о социальном кризисе во Франции, волнениях в других странах и революционном настроении молодёжи. Оливье Ассайас показал, как соотносится деятельность элиты и рабочего класса. В картине много локаций, но при этом не хватает яркости, художественного решения и общей напряжённости.Публика продолжает ждать новый фильм Ким Ки Дука «Пьета». У корейского режиссёра был творческий кризис, но постепенно он возвращается к своему обычному рабочему ритму. Картина названа в честь шедевра Микеланджело – скульптуры «Пьета», которая изображает Деву Марию, держащую мёртвое тело Иисуса Христа. Лента расскажет о жестоком человеке, который занимается сбором долгов. Встретив загадочную женщину, утверждающую, что она его родная мать, он находится в растерянности и не знает, что ему делать, ведь женщина должна его нанимателю. Новый фильм Ким Ки Дука появился после долгого перерыва, поэтому зрители ждут картину с нетерпением.

К чуду,

Полный беспредел,

Пьета,

Мастер

Терренс Малик,

Оливье Ассайас,

Ким Ки Дук,

Такеши Китано,

Пол Томас Андерсон

Новинка

Brother, 2000

When Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence producer Jeremy Thomas came knocking to offer Kitano a Hollywood-based feature of his own in 2000, the director lapped up the opportunity on the condition that he could retain full creative control. The resulting film, Brother, remains something of an oddity in his back catalogue. To this day his only feature made outside of Japan, it follows Kitano’s archetypal, introverted gangster as he builds an empire in the unfamiliar setting of Los Angeles.

Rather than attempt to adapt his filmmaking craft to the Hollywood mould, Brother merely swaps Tokyo for LA and throws in a few American actors as an attempt to capitalise on the newfound popularity of Japanese cinema abroad. Kitano’s legendary lack of patience feels like it’s on full show here. While his economical shooting style had captured moments of magic so often before, the scant rehearsals and one-take filming are less conducive with Brother’s B-movie cast and clunky script.

‘No pressure’

«I don’t intend to hit my films or make money from now on, so I’m not moved by anything» about Cannes. «I don’t feel pressure,» he said.

Begun in the late 1980s, when he was already famous in Japan as a comedian and burlesque television host under the pseudonym «Beat» Takeshi, his career as a director revealed a completely different Kitano, deep, sensitive and tortured.

He was spotted abroad from his film «Sonatine» (1993) and won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1997 with «Hana-bi», diverting in his own way the traditional Japanese genre of «yakuza eiga» (yakuza films).

And in «Zatoichi» (2003), his biggest commercial success to date, he was already dusting off samurai movies, another classic Japanese genre.

«Kubi», in which Kitano also plays, is thus his second period film, and promises a very raw and personal version on a central event in the history of Japan but always shrouded in mystery: the «Honno-ji incident» in 1582, a fatal plot to the most powerful warlord of the archipelago, Oda Nobunaga.

A big-budget production by Japanese standards (1.5 billion yen, or more than 10 million euros), «Kubi» is also Kitano’s most expensive film to date.

«I wanted to try something on a larger scale,» he explains, admitting that he would have liked «three times more» budget and extras.

Sonatine, 1993

While the detached hard-man of Violent Cop is straightforwardly transposed onto disenchanted yakuza boss Murakawa in Sonatine, the film distinguishes itself from its predecessor through its sudden tonal shift in the second act. Ditching a grisly backdrop in Tokyo gangland, the cast of misfit thugs spend much of the film’s runtime on an idyllic beach paradise awaiting orders, in an unconventional subversion of the gangster genre’s established tropes.

While Kitano claims that the colourful beach vistas that often crop up in his films are a symbol of impending death, the most obvious effect of Sonatine’s peaceful central setting is that it completely disarms the viewer for the film’s violent conclusion.

Buy This Title on Amazon by clicking on the image below

After a meeting at the headquarters of the Sanno-kai, one of the largest crime syndicates of the region, Ikemoto (Jun Kunimura), one of the many under-bosses, is given the order to sever his ties with gang leader Murase (Renji Ishibashi). Considering the two have spent time in jail together and have become brothers, Ikemoto decides to give the matter over to his subordinate Otomo (Kitano), who is supposed to start a conflict with Murase’s gang to keep up appearances with the Sanno-kai, while also not angering him too much and endanger their partnership.

However, after a minor incident at one of Murase’s night clubs, the affair quickly gets out of control, with Otomo and his men finding themselves as pawns caught in the middle of diverting interests. As his boss attempts to balance his partnership with his brother and his status within the clan, the leader of the Sanno-kai apparently has other plans, which involve getting rid of the competition and an under-boss who has become too weak over time. Even though he tries his best of setting the record straight, Otomo realizes he has become the scapegoat for all parties involved, which starts an all-out war within the yakuza clan.

In many ways, what Kitano has accomplished with the “Outrage”-trilogy is creating the anti-”Godfather”. While Francis Ford Coppola’s gangsters, or for that matter even the ones in Kinji Fukasaku’s “Battles Without Honor and Humanity”, had principles and character traits which qualified them as heroes, for example, their family bond or their struggle to survive, there is no such thing in “Outrage”. The various leaders and their thugs, no matter what their position is within the yakuza hierarchy, are indistinguishable in their greed, lust for power and, most significantly, their cold-heartedness. You might say that even fans of the director’s former ventures within the genre will be disappointed in “Outrage” (and its sequels) considering there is nothing elegant or melancholic about these gangsters who are brutally calculating their next move, and whose fate is decided by their position within the food chain of the clan.

This sobering and often brutal look at the world of the yakuza is reflected in the movie’s aesthetics, its score and the performances. Keiichi Suzuki’s score, a blend of electronic tunes and rhythms, highlights the mood in this world we get a glimpse of, where a life means nothing and everyone, also innocent bystanders, can become victims if it serves the power schemes of those in charge. Fittingly, Kitano and cinematographer Katsumi Yanagishima rely on blue filters along with very little camera movement to portray this world, as well as the increasing turmoils later on as some of the plans and schemes backfire and upset the order of the clan. Emphasized by the color scheme of his costume, Otomo remains one of the only exceptions within this ensemble of gangsters, as he voices his growing impatience with weak leaders, broken promises and how his status within the Sanno-kai makes him vulnerable. Aside from Kitano’s performance, perhaps the most noteworthy are Kippei Shinna as Otomo’s right-hand man Mizuno and Tomokazu Miura as Kato, the assistant to the boss of the clan.

In conclusion, “Outrage” is a great gangster movie, showing there is still some interesting themes and ideas which can be told within the genre. Takeshi Kitano gives his viewer a cold, often violent glimpse into the world of crime, its schemes and character traits, which more than once seems to mirror the hierarchy of a modern company.

Do «what I like»

Kitano wrote a synopsis of «Kubi» 30 years ago, at the very beginning of his directing career. But it was only after writing and publishing an eponymous novel in Japan in 2019 that the machine to make the film happen.

But how to appropriate a genre sublimated by Akira Kurosawa (1910-1998), the great Japanese master behind «The Seven Samurai», «Kagemusha» or «Ran», and of which Kitano is himself a fervent admirer?

«I tried not to watch the battle scenes in Kurosawa’s films to avoid them influencing me,» he explains. «I hate being influenced.»

Loyalty, betrayal, Japanese codes of honor: we find in «Kubi» themes dear to Kitano, who wanted to expose this troubled period of Japan in a much darker, bloodier and intimate aspect than in the usual watered-down Japanese productions.

«I just do what I like (…). I don’t care too much if viewers are going to think +That’s Takeshi+’s style,» says the director, who «doesn’t care completely» about his status as a movie legend.

«I would be very happy if a work that I filmed with detachment received a good reception again, but that does not mean that I will try to please,» says this eternal libertarian.

2023 AFP

Takeshi Kitano: The Auteur

Sonatine is a yakuza film that one could describe as a deconstruction of the yakuza genre. There is violence, bosses, codes of ethics, big tattoos, and illegal activities. All that’s lacking is a character arc. Yakuza films typically share a common theme of redemption or ambiguous justice.

Sonatine (1993) source: Miramax

Sonatine (1993) source: Miramax

Most films introduce their protagonist and show their connection to the Japanese underworld, whether it be a law enforcer or gangster. Then an unjust villain commits a tragedy and the protagonist (usually) performs retribution to save the day. However, in a just world, violence is a crime that cannot be rectified so our protagonist faces their demise; the vicious cycle of yakuza. Of course, this heavy summarization can be argued and certainly has room to be expanded on, but for the sake of brevity, this is the framework this discussion Sonatine will be based on.

It is important to note that typical yakuza genre is under the guise of a serious tone. For example, Battles Without Honor and Humanity (1973-1976) is a film series where the material is an adaptation of real-world events and thusly the films have an air of documentary. As if to say, “this is a real story that the audience should take seriously, crime does not pay.” Sonatine takes that sentiment and shrugs its shoulders.

The Stylings of Violence

Murakawa (Kitano) is a Tokyo-based enforcer who’s tired of the yakuza lifestyle and wishes to retire. Unfortunately for him, his boss tells him that his gang must go to Okinawa to help settle a treaty between the two allies, the Nakamatsu and Anan clans. Once settled in a temporary office, Murakawa feels unsettled believing his boss sent him there to be killed. His suspicion proves correct when his office is bombed, forcing him and the survivors to lay low at a beach house.

Sonatine (1993) source: Miramax

Sonatine (1993) source: Miramax

The violence shown in Sonatine has the cathartic explosivity of cracking your knuckles. Actors stand in place with blank expressions as they shoot at each other only because they do happen to be holding guns. Conversely, there is action in the form of beach games that Murakawa and his gang play while in hiding. Such as shooting bottle rockets at each other or performing a life-size replication of a tabletop sumo game. These two modes of action clash against each other in what makes for a transgressive mood.

Transgressive in a way that makes it feel weird to say that the film is a yakuza film. What starts as the tale of a veteran yakuza doing one more job before retirement, becomes a vignette for a man expressing his desire to get out of his life in an almost depressing manner. Probably the film’s most famous scene, when Murakawa plays Russian roulette with two others on the beach, features a final shot landing on Murakawa and it is believed he’s going to die. However, the gun was empty the whole time and no danger was present. Later that night, he has a dream of the same scene but the gun is loaded.

Sonatine (1993) source: Miramax

Sonatine (1993) source: Miramax

The thread grounding the film is the violence that’s made from Murakawa; he is a violent man whose whole character is centered around it. It is fitting that the central character with the least lines expresses himself the most in action. The rejection the film casts against the staples of traditional yakuza film is skewed in such a way to make light of the genre altogether.

Similar to what Hideaki Anno did to the mecha anime with Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995-1996), Takeshi Kitano did to the yakuza film with Sonatine. Both understand the lineage of the genre space they are inhabiting so they can turn those conventions on its head.

Sonatine: Final Thoughts

This only leaves the question of how an audience in 2019 can think of this film released over 25 years ago. Well, there is the pleasing retro-ness of the ’90s being on prominent display with Ryōji (Masanobu Katsumura) whose short shorts and colorful shirts give inspiration for summertime looks. Or the meditation one can have on beaches in the canon of cinema; this is certainly my favorite beach movie! Whatever the impression left on a modern audience, the sensation of rejuvenating sorrow as the final credits roll is one that is certainly in limited stock options.

Sonatine makes me feel like I am shooting a big gun whilst my hair is blowing in the wind on a beach with my dearest friends telling me that my life is important. Do you have a film that makes you feel joyful yet melancholic? Let us know in the comments!

Sonatine was released in the US on April 10, 1998. More release dates can be found here.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema — get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Hana-bi, 1997

Like most of Kitano’s early works, Sonatine failed to find an audience at home – but after being picked up for the London Film Festival and nominated for the Best Director Award at Cannes, the director was beginning to make an impression abroad. Film composer Joe Hisaishi, best known for his whimsical scores to Studio Ghibli animations, had picked up a Japanese Academy Award for his score. And with regular actors Susumu Terajima (Ichi The Killer), and Ren Osugi (Cure) now forming a recognisable cast of faces in Kitano’s universe, the director was poised for a breakthrough.

The culmination of all Kitano’s filmmaking experience came in 1997, one of the most significant years in Japanese film history. As Naomi Kawase and Shoehei Imamura received major honours at Cannes (for Suzaku and Unagi/The Eel respectively), Kitano’s Hana-bi completed an unlikely triplicate when it won Japan the Golden Lion at Venice. It was only the second Japanese film to win top honours since Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon won the award in 1950.